As organised crime in Sweden has become a part of everyday life the prison system faces challenges. More concerning, younger kids have been an increasingly popular targets for gang recruitment because of the unique advantages their age holds.

Peter Svensson, of the Brotherhood Wolfpack gang and current co-founder of Initium Skyddat Boende, discusses his experience with criminal networks. Photo credit: Hannah Straily

By Natalie Rocha and Hannah Straily

Sweden used to be one of the safest countries in the world according to the European crime index up until 2015, but new data from the police of shootings and explosions everyday shows it has rapidly become recognised for its organised crime.

According to a recent Swedish police report, as of November 30 there were 346 shootings in 2023, 50 resulting in fatality and 143 explosion attempts or successes. The detonations most often occur in the metropolitan regions of Stockholm, south and west, where most criminal networks are located.

A relevant concern for Sweden is the ongoing recruitment of minors.

“Children aged 12–15 are recruited into criminal networks by other young people who are often 15–20 years old,” according to a report from the Crime Prevention Council, Brå.

Snow covered playground located in Husby, neighbourhood north of Stockholm. Photo credit: Natalie Rocha

Now more than ever, Sweden’s legal system means children and teenagers are being targeted to join gangs and commit crimes through organised networks.

Ahmed Abdigadir, a journalist for a daily newspaper based out of Stockholm called Svenska Dagblade, specialises in reporting on organised crime in Sweden said that is exactly why young people are getting recruited and are susceptible to joining.

Ahmed Abdigadir, a journalist for a daily newspaper based out of Stockholm called Svenska Dagblade, specialises in reporting on organised crime in Sweden said that is exactly why young people are getting recruited and are susceptible to joining.

The overall rise in crime has been a topic in local papers daily, even multiple times a day on occasion.

“The reputation, I don’t care. I don’t care if it’s bad, if we get bad press. So, what, people are dying, that’s more important, in my opinion,” said Abdigadir.

Abdigadir said there seems to be a trend of middle-class people actively pursuing a career in criminal gangs, but before it was people from segregated areas.

“People like me, you know, from Somalia, from Kurdistan, from Iran, you know, foreign-born people,” said Abdigadir.

Abdigadir, a Stockholm native grew up in the metropolitan neighbourhood called Husby.

Stockholm’s danger zone

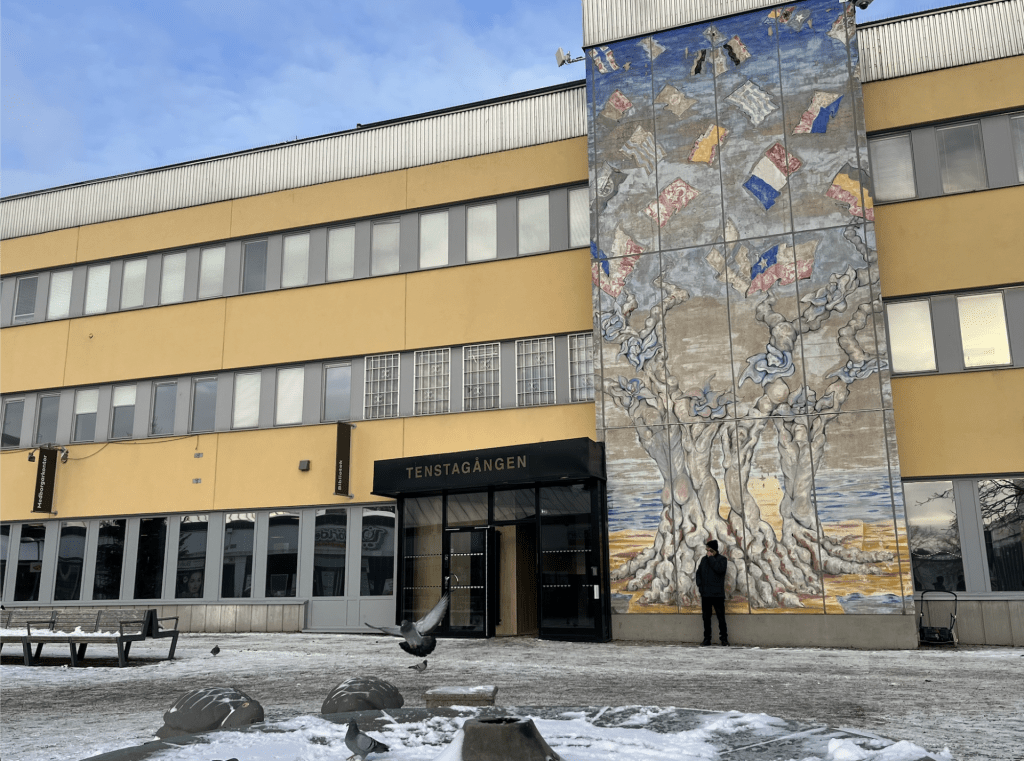

Husby is one third of Järva, an area outside central Stockholm. Järva is made up of three northern neighbourhoods including Rinkeby and Tensta. Järva has a reputation for being the most dangerous area in Stockholm.

Map of Järva

Järva is known for its high-risk crime rates and as a rural outskirt is home to many migrant families but racial disparity does not seem to be the biggest factor of gang activity for community leaders.

Tomas Almgren, a project manager for Fryshuset, an organisation across Sweden that provides activities and schooling for youth said, “our view is not that it’s ethnic, it is not an ethnic thing that people from Africa and the Arab world are more criminal than Swedish. It’s all due to the lack of money.”

But in a press release by the Swedish police on November 21 said, “this is a problem that exists in all social classes. Recruitment is very fast – once you have agreed to an assignment, it can be very difficult to withdraw.” Sometimes young gang members are abandoned by their recruiter leaving them lost.

Peter Svensson 45, an ex-gang member of the Brotherhood Wolfpack, did not officially get recruited until he was 20 but he did start networking in organised crime at age 12.

Svensson stole a bike and sold it to two men who praised his skills. He offered to be back at the same time the next day with two more bikes.

For Svensson, the money was not what enticed him, but rather the recognition and affirmation he got was his motivator to engage in criminal activity. He worked closely with a network of criminals until he officially joined the gang in 1998.

“That’s why you use younger [people], for bigger [crimes].” “If you’re 13 and get caught carrying a gun, the penalty is much less than if you’re 30. The same with drugs,” Almgren said.

But youth in gangs has evolved, it is not just narcotics and putting a hit on someone. Children get online and commit fraud through social media apps and SMS. Elderly people have especially been the target of this kind of fraud.

“Criminal people are looking on Snapchat for young kids to take a large sum of money, so that they can commit fraud against elderly people,” said Abdigadir.

“We don’t do enough”

Fryshuset is one of Sweden’s largest organisations that helps young people. The Stockholm location operates as a school where youth can explore different interests and hobbies during the daytime. Then later in the afternoon the house changes and anyone involved in dance, music, basketball or skating comes in.

Entrance to Fryshuset at the southern Stockholm location. Photo credit: Natalie Rocha

Programs and organisations such as this cannot guarantee that kids stay away from criminal paths, though they can help redirect some.

“So, you try to get to young people by doing positive things, because young people don’t want to look upon themselves as a problem,” said Almgren.

The Swedish Police website has a section where parents can read about warning signs to look for to prevent their kids from being exploited by criminal gangs.

Gunnar Appelgren has worked for the National Police Department in Stockholm and the Uppsala area for 39 years. These past 25 years he has held the position of detective superintendent.

“We don’t do enough of course. It’s like this now, we have done too little to prevent the kids from getting into the criminal gangs,” said Appelgren.

Stockholm police station entrance. Photo credit: Hannah Straily

Overcrowded and underfunded

Minors from age 15 to 18 serve half their sentence and most times are let off with a warning. That is the appeal for recruiters, to involve young people who seek the short-term benefits of committing crimes such as money, clothes and notoriety in their community. Serving a fraction of a sentence is worth it to these kids. Cases where kids under the age of 15 are committing crimes are dealt with by the social department.

Prisons in Sweden work around rehabilitation programs, offering a school-like structure where inmates learn practical life skills and occupation related courses can be taken.

Sweden is now experiencing overcrowding in prisons which has escalated to the degree that inmates must share rooms, which is not normal. Typically, a room is only occupied by one person. According to the World Prison Brief the population of Swedish prisons increased by nearly two thousand from 2017 to 2020.

“[The] police are getting better. I mean, they’ve caught a lot of people,” said Almgren about the reasoning behind this.

Tomas Almgren outside of the southern Stockholm Fryshuset location. Photo credit: Natalie Rocha

The prisons are divided up depending on the type of crime committed. There are prisons for crimes such as domestic, child and drug abuse and prisons that house offenders of gang related crimes such as armed robbery, disbursement of narcotics and murder.

Malou Wikström worked at these types of prisons over the course of three years. In 2017 she worked at a maximum prison for those charged with crimes of a sexual nature for six months. Then she worked as a guard on the street for around a year before working for the solitary wing at another maximum prison with inmates charged for gang related crimes.

Inmates have become unhappy with the overcrowding to the point where several years ago two of Wikströms old colleagues were taken hostage by prisoners. Even though they were in jail, they still cared about the quality of life in their current situation.

“Imagine having two people who are capable of great violence locked up in a very small room together for twelve hours every night with the same person. If they don’t click, you can have a prison murder,” said Wikström. “So far, we haven’t had that many that I’ve heard off. But I think it’s a matter of time.”

On top of the overcrowding, prison systems are also underfunded.

“We are catching criminals much more now and they go to jail, and at the same time they don’t have this money for the correction authority… So, they have not had the possibility to develop their work,” said Appelgren.

According to a study published early in 2023 by Swedish researchers Xiang Zhao, Per-Åke Nylander and Anders Bruhn, these types of aggressive behaviour can have a negative impact on prison officers. This is especially the case in understaffed prisons.

“I think I’ve learned more about people, and the sad truth of how hard it is for people to get out of gangs,” said Wikström when talking about one of the biggest things she learned from working at a prison.

The reality of leaving a gang

An inmate that Wikström worked with expressed how he wanted to get out but could not. In order to keep him and his family safe, he was stuck in a repetitive cycle of committing crimes where he felt like there was no way out.

Getting out of gangs can be a difficult process, it is a taboo subject to talk about in prisons. “[As a gang member] you don’t really say that you want to leave, it creates insecurity in the gang,” said Wikström. Word has a way of traveling to outside of prisons, which could put those who want to get out in danger.

In early 2006 Svensson was in and out of jail for a couple months before he served from June 2006 to 2009 for gang related crimes. While in prison, every two weeks a social worker would come to talk with Svensson. Through these visits he was connected with a therapist and others who believed that he would be able to leave his gang and re-enter society.

Svensson decided to leave Brotherhood Wolfpack when he was 31. He had a friend send the letter to ensure he would not back out of his decision, and so the gang would not be aware of his location in Stockholm.

“It takes a month before I get an answer. And under this month, my feeling was that I need to pay, maybe I get killed or maybe I need to do something for the gang, like kill somebody,” said Svensson.

Peter Svensson holding a shirt designed by Homeboy Industries. Photo credit: Natalie Rocha

Brotherhood Wolfpack responded to his request to leave with bribes to keep Svensson in the gang, but he refused and found comfort in his decision to leave a life of crime and start over in Stockholm.

“I’m nobody. It was a good feeling that nobody knows me, but I’m also very alone,” said Svensson, reflecting on his choice to leave what he considered a community.

Almgren mentioned that other reasons people want to leave gangs is because they are scared or they did not make as much money as they thought they would. The older you get the more likely it is that people might want to leave a gang.

Why is this happening?

“Because it’s so easy. We don’t have the proper legislation to deal with this… And I think we’ve gotten a little comfortable with being so safe,” said Wikström.

Sweden has ranked within the top four countries of Europe’s Crime Index since 2016, prior to that it was closer to the middle. The uptick in crime was unexpected. Almgren even says that he does not think the gangs themselves expected it.

Wikström has lived in Sweden her whole life, she remembers when she was younger even the sight of a police car was rare. When her mother was a child, there were only three murderers in Sweden.

“It’s common to have 12 shootings per week, at minimum… And Sweden is not a big country. We have 10 million people living here,” said Wikström.

Despite this there have been some improvements, such as the overcrowding in prisons due to more criminals being caught. Fryshuset itself does not fully focus on outreach towards young criminals. However, Svensson was a part of a program that branches off Fryshuset called EXIT.

EXIT focuses on those who are involved in radical groups or violent gangs, helping them leave.

Tomas Almgren talking to a co-worker at the reception desk at Fryshuset. Photo credit: Natalie Rocha

Interview with Tomas Almgren: Fryshuset and EXIT