An event that remains in the memory of the Czech public even after decades. In Nové Heřminovy there is a fight against the construction of the water reservoir, meanwhile, the citizens of Karlovec still bear the consequences of a similar event. Supported by a newly planned reservoir in the same region a new wave of emotion comes to the surface. Prompting a discussion on the price of an alleged progress.

By Romana Ronja Ptáčková

The fate of the Czech village Karlovec lying on the confluence of the Černý potok and Moravice was decided when it was chosen for a planned water reservoir Slezská Harta. The construction planning started in the 1960s in response to rising water demands from industries and residents in Silesia and Moravia and it would result in flooding Karlovec. In the days of the hard-ruling communist regime in the Czech Republic, the notion of protesting was not widely considered.

“We did not like it much, but what could we do? One must have to hold his mouth shut – as they say. It was not like now, that people could protest,”

says Marta Zlámalova who grew up in the village.

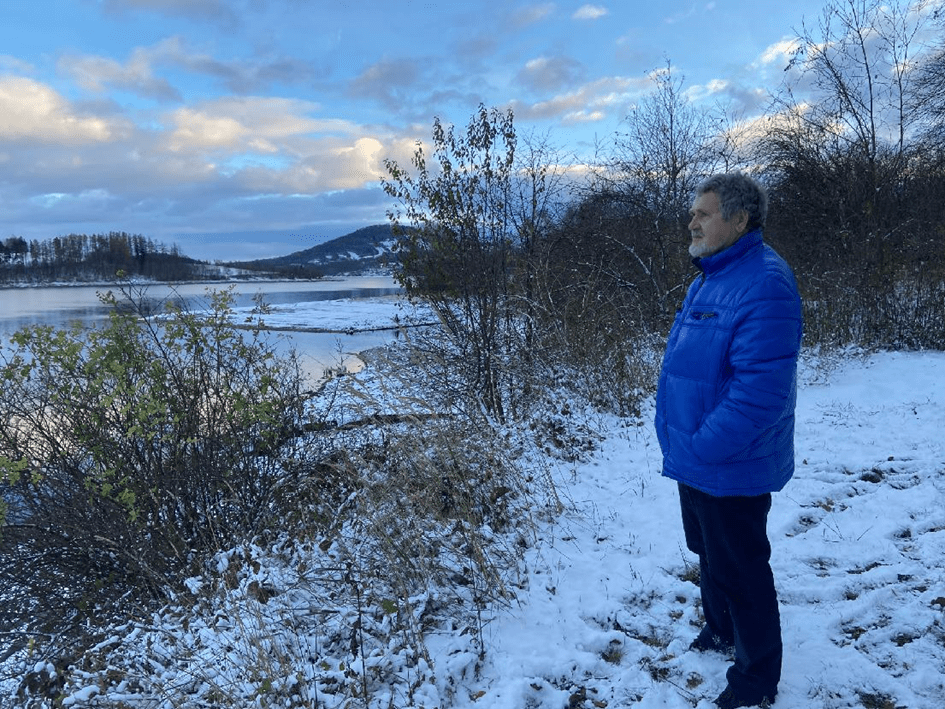

The former residents of Karlovec observe the situation echoing in yet another Moravian village and polemize about what could happen if circumstances were different back then. Jiří Doležel is one of them.

“I sympathize with the people of Nové Heřminovy. At this time, it is possible to speak against something and win. I wish they didn’t need to go through the same things we did.”

For years, the residents of Karlovec endured the looming threat of the dam, yet the idea that they would one day be forced to abandon their homes remained an unimaginable prospect. When the day finally came many bore it with sorrow and the fear of an uncertain future. Zdeněk Hublík, whose whole family lived in the village remembers the day well.

“My parents got into debt so they could buy a house in 1948. When they were told that the dam would be built, and they would need to move out it was the biggest trauma in their lives. They were a certain age at that time, and it was a struggle for them to acclimate to a new place. They never got used to their new house. I remember when the moving truck came and took my parents with their dog and cat away. That was the hardest of times.”

he confides emotionally.

Inadequate compensation

The residents were relocated to apartments in the town of Bruntál and provided with financial compensation; however, many found the compensation to be inadequate. Having lost their family homes and plots of land, the amount they received fell far short of enabling them to acquire new properties. Hublík recalls the real estate valuation process as notably ambiguous and unjust, noting that one evaluator revealed they were instructed to propose the lowest amounts in order to cut costs. In the process of dam construction, this is not unusual.

„Cash compensation is a principal vehicle for delivering resettlement benefits, but it is often delayed and, even when paid on time, usually fails to replace lost livelihoods “

states the World Commission of Dams in its 2000 study focusing on human rights when it comes to dam construction.

That is the case of the Slezská Harta water reservoir as well as many other affected places around the globe.

Sacrifice in the name of progress?

While Slezská Harta brings numerous benefits concerning the drinking water supplies and the economic growth of the region. Previously, the adverse consequences of dam construction were often underestimated and inadequately addressed.

“Historically, the negative impacts of dams have been underestimated and the values of free-flowing rivers – rivers whose flow and connectivity are largely unaffected by human-made changes, have been underappreciated. Today, free-flowing rivers are needed more than ever to reverse nature loss, sustain groundwater recharge and deltas, and help humans adapt to climate change, “explained Claire Baffert, senior water Policy Officer at WWF.

In the contemporary landscape, securing construction approval has become a notably challenging process.

“It’s not the 1950s anymore, it’s become a little more difficult for the dam builders, because today they have to look for other reasons for construction and challenge counterarguments, which, as the European Union has shown, they don’t quite manage,”

communicates an environmental activist and s representative of the movement Duha Jeseníky Ivo Dokoupil.

He addresses the EU Biodiversity Strategy and its initiative to preserve natural waterways.

Baffert from WWF described it as a comprehensive long-term plan to protect nature and reverse the degradation of ecosystems that acknowledges the need to accelerate efforts to restore freshwater ecosystems.

The residents of Karlovec accepted their fate

In the year 1997, the construction of the dam was completed, and the Moravian-Silesian Region could welcome its new reservoir. All that remained of the village Karlovec was the Church of St. John of Nepomuk and the adjacent cemetery, where many of the village’s residents had their relatives buried. Despite the lingering grief over their displaced homes, the residents view the dam with optimism, acknowledging and cherishing its aesthetic allure. It is still a home, after all. Zdeněk Hublík is one of those who like to come back.

„We are so very glad to remember Karlovec and we do it almost every day, even though it has been 30 years since we left. Every time me and my family drive along the water, we look at the surface, try to see the bottom, and reminisce about who lived where. We will remember till the day we die – as they say. “

The fate of Nové Heřminovy remains uncertain. Only time will tell if the unwavering efforts of its residents can prevent tracing Karlovec’s path.