As defamation is re-criminalized in Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Republika Srpska entity and a controversial “foreign agent” law awaits final approval, activists and watchdogs say they’re feeling the pressure. The EU, UN and Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe have all called on authorities to halt the legislation – so far to no success. Activists, meanwhile, are bracing themselves, fearing fresh crackdowns around the corner.

By Cecilie Bjerre Hemmingsen, Oskar Hammer Sylvestersen and Jack Wilson

It’s not like UNSA Geto hasn’t been threatened before. One of few LGBT-friendly spaces in Bosnia and Herzegovina’s Republika Srpska entity, the art gallery and event venue faced homophobic attacks earlier this year.

“If you are an artist, your first exhibition is probably going to be here,” said human rights activist Vesna Malešević, a member of the UNSA Geto NGO.

More than just facilitating art exhibitions and events, Malešević calls UNSA Geto an activist organisation, aiming for the democratisation of society through art and culture.

In March, a group of about 30 young people attacked the NGO’s building after authorities in the largely autonomous region of over a million people made several comments disparaging plans to host a pro-LGBT event. The “hooligans,” as Malešević called them, smashed windows and destroyed the gallery’s sign. Malešević said she and her colleagues filed a police report but didn’t hear back from authorities.

This attack was the first physical attack UNSA Geto has experienced, Malešević said. But now, she’s focused on a different type of attack – a proposed law she fears will target her organisation’s activities. If passed, the law will label non-profit organisations receiving international funding as “foreign agents,” risking their credibility. It will also prevent them from engaging in political activities. What exactly constitutes a political activity is not yet clear to activists like Malešević.

The “foreign agent” draft law was one of two in the Republika Srpska to draw widespread condemnation this year. The other, which passed this July, criminalised defamation, reversing its decriminalisation two decades earlier. The European Union has characterised both laws as examples of “democratic backsliding” – a serious charge given Bosnia and Herzegovina’s status as a candidate for EU membership.

While organisations including the EU, UN and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) have joined in calls for the controversial laws to be withdrawn, local activists and journalists — key players in a functioning democracy — say they don’t yet know how the laws will impact them. With confusion around the definition of a political activity, activists and journalists who receive international funding are questioning whether their work might soon become illegal.

| Republika Srpska and the Bosnian War The largely autonomous Republika Srpska is an enduring legacy of the Bosnian War, which saw fighting between Bosnia and Herzegovina’s three main ethnic groups: Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats. Following the secession of Slovenia, Croatia and Macedonia (now North Macedonia) from Yugoslavia, Bosnia and Herzegovina declared its independence on 3 March 1992 after a referendum. In response to the declaration, Serbian forces invaded the newly declared country. A bloody war and genocide ensued, which saw 100,000 deaths, 80,000 of which were Bosniaks. The war ended in December 1995 after US-led NATO forces intervened. Peace negotiations resulted in the Dayton Accords, which created the constitutional framework of the modern state of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It divided the country into two entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Serb-dominated Republika Srpska. Though comprising one sovereign state, both entities maintain a high level of autonomy. |

Controversial legislation

On 31 October 2022, Republika Srpska President Milorad Dodik posted a thread on X (then Twitter) calling for the reintroduction of the crime of defamation into the criminal code. By March 2023, the entity’s National Assembly had introduced a draft law, which passed 20 July and came into force 26 August. In a joint statement published that very day, the EU, UN, Council of Europe and OSCE expressed “dismay” at the law, saying it threatened the work of “journalists, human rights defenders and other civil society actors.”

Though criminal defamation exists around the world, including in many western countries, such laws are typically “very rarely used,” said Igor Ličina, OSCE Bosnia and Herzegovina Program Officer for Fundamental Freedoms. The OSCE, made up of 57 participating states, mostly in Europe, has a mandate to track human rights developments in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Igor Ličina, National programme officer, fundamental freedoms – human dimension/human rights, OSCE. Image: Oskar Hammer Sylvestersen

“All international standards speak in favour of decriminalising insult and defamation,” Ličina said. In the months since the law’s passage, Ličina said authorities have registered 27 criminal defamation cases. Since the cases have yet to reach trial, their contents are unknown, he said. Still, Ličina said the OSCE suspects some of them will target human rights defenders and journalists.

Drawing similar ire from groups like the EU and OSCE is the “foreign agent” draft law, which passed 28 September. The law requires final approval in the Republika Srpska National Assembly before taking effect. It would brand nonprofits receiving international funding as “foreign agents.” The nonprofits would be banned from engaging in “political action” or “political activities,” according to a legal opinion drafted by the OSCE alongside the European Commission for Democracy Through Law.

Though the law exempts certain activities from the ban, including the protection of national minorities and the fight against corruption, the opinion points out that human rights and rule of law advocacy are both missing from that list. Human rights and rule of law campaigning risk being classified as “political activities” and therefore subject to restrictions, the opinion warns.

The law threatens activities that “we are doing all the time,” said Dragana Dardić, who heads the Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly chapter in Banja Luka, the Republika Srpska’s largest city. From 1997, the Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly lobbied for the recognition of domestic violence in the Republika Srpska’s criminal code. Lawmakers made that change in 2000. Under the proposed law, such advocacy “would be forbidden,” Dardić said.

“Who will want to work for organisations that are officially labelled as agents of foreign influence?”

The Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly established itself in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1996, following the Bosnian war. At the time, the organisation aimed to reassemble Bosnia and Herzegovina’s divided population.

Nowadays, “our aim is to encourage different marginalised groups in society, particularly women, but also youth and persons with disabilities, to be more active in political and public life,” Dardić said. She said the NGO aims to protect and affirm human rights.

The organisation receives its funding from foreign donors, including the EU, UN agencies and the Dutch government. It receives no local funds, though Dardić said her organisation has applied unsuccessfully for government funding. Reliance on foreign donors is common for many NGOs in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which Dardić suggested shows the very purpose of the “foreign agent” law is to limit the work of activists like herself.

Unable to find funding locally, Dardić said the Helsinki Citizens’ Assembly will find its activities restricted simply because it receives funds from the only donors willing to give – international donors.

With activities already threatened by the criminalisation of defamation and with the possibility of further restrictions on the horizon, “the circle will really be closed… we will not have space anymore to work,” she said.

Dardić said she also fears the restrictions spreading to the rest of the country, also affecting activists and journalists outside of the Republika Srpska. Ivana Korajlić, Executive Director at Transparency International in Bosnia and Herzegovina, said she shared that concern.

Transparency International considers itself a watchdog against corruption and human rights violations. Such work is already difficult in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Korajlić said, but will only become more difficult as the new laws enter into force.

If NGOs like her own are listed as foreign agents, she expects difficulties when hiring employees. “Who will want to work for organisations that are officially labelled as agents of foreign influence?”

New restrictions could hinder day-to-day operations, blocking some activities altogether and slowing down others. “You cannot perform specific activities. You have to submit various reports to the government, which require a lot of resources,” Korajlić said.

“You can have unannounced inspections in your offices that can further hinder your work.”

Smaller organisations will have a harder time, Korajlić said, as they might not have the resources to comply with administrative checkups and reports.

Malešević said she already finds space for her work limited, with the government often accusing pro-LGBT organisations of undermining traditional values. Once located in the city centre, in a space provided by the municipality, UNSA Geto relocated a decade ago after the municipality accused them of being too loud.

Malešević called her organisation a “little hub for everybody who wants to do something on the social or artistic level.”

Its most recent exhibit featured the work of Obrad Cešić, a Serbian artist out of Belgrade. Called “Pleasant work,” it “represents the victims of the historical development that led to marginalisation of the workers,” she said. The exhibit consists of mannequins strewn on the ground, covered in rubble. Their heads are covered by white cloth and they wear workers’ gloves.

“Pleasant workers” by Obrad Cešić was exhibited from November 20th until November 30th 2023 Image: Oskar Hammer Sylvestersen

Like other activists, Malešević said she was unsure how the “foreign agent” law will affect the NGO’s work. “We don’t know what is going to happen,” she said.

As working conditions for activists threaten to worsen, Korajlić said she feels pessimistic about the future for activists like herself. Still, she emphasised that she would keep fighting for change.

“When you get into this, you cannot just give up, despite being very pessimistic. You still feel the need to do something.”

Journalists under pressure

As the criminalization of defamation and “foreign agent” draft law draw concern from activists, journalists, too, say they’re under pressure. Even if never criminally charged with defamation or labelled a foreign agent, journalists “feel a lot more threatened. They feel a lot more insecure,” said Denis Džidić, Executive Director and Editor of the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Balkan Investigative Reporting Network publishes investigations out of all former Yugoslav countries, employing about 15 journalists in Bosnia and Herzegovina, including several in the Republika Srpska. Its reporting has documented the post-war justice process, caught government agencies illegally spending millions of euros on high end limousines and revealed widespread election irregularities.

Denis Dzidic Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN), BIRN BiH Executive Director and Editor. Image: Oskar Hammer Sylvestersen

Though funded entirely by donors outside of the country, the “foreign agent” law won’t impact the NGO’s status, because it’s registered at the state level. Still, Džidić suggested similar laws might appear in other jurisdictions. “It’s most certainly a worrying trend and it could be replicated,” he said.

If the law comes into place, Džidić said nonprofit news outlets registered in the Republika Srpska could work around the law by re-registering in other jurisdictions. But some might interpret such a move as evidence that the outlets are foreign agents, he said. Such impressions are “very difficult to fight against. I think [Republika Srpska politicians] win in a lot of ways the moment they adopt these laws,” Džidić said.

‘It’s really, really hard to see any future for Bosnia’

In another country, Téa Kjajić might be considered a future leader. The 22-year-old activist, who studies at the University of Banja Luka, is the Western Balkan regional coordinator for Students for Liberty, a network of libertarian student organisations. She writes opinion pieces and organises political events.

But with the structure of the political system in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the recent developments in the Republika Srpska, Kjajić said she’s concerned about consequences if she organises events at her university. She fears different treatment from professors and developing a bad reputation. The “foreign agent” law isn’t helping, she said, because it gives the impression that activists like herself are foreign agents.

“In my university, many people support the system that we live in, so it’s really hard to make changes when the students support it,” said Kjajić.

In general, she said she finds it difficult to even get permission from the university to engage politically. Her colleagues abroad “usually don’t face those problems,” she said.

In a few years, Kjajić hopes to settle outside of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Amidst what she considers an erosion of freedoms, she said she doesn’t have hope for improvements in the near future.

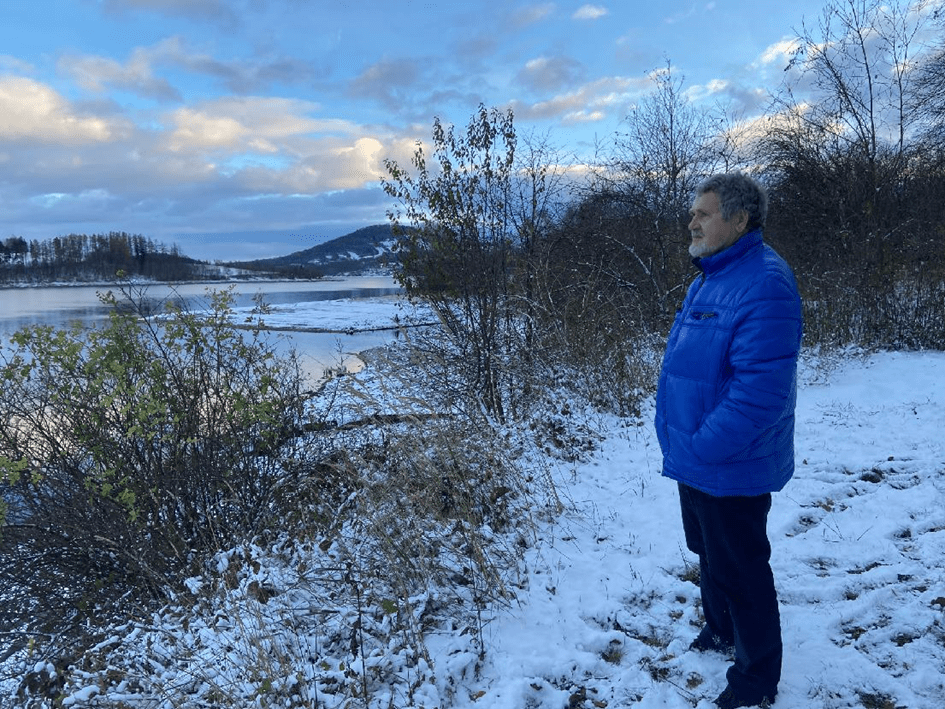

“We are lacking people and activists,” said Nela Porobić Isaković, an activist living outside of Sarajevo, the country’s capital. Porobić holds a leadership role in the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, an international feminist organisation, but also organises local campaigns and actions. Activists are leaving Bosnia and Herzegovina as part of a larger trend of emigration, “because it’s really, really hard to see any future for Bosnia,” she said.

While many leave for economic reasons, others tell her they “cannot deal with this country anymore,” she said. “We have a lack of doctors, lack of paediatricians. My kids go to school and there’s a noticeable lack of personnel.” Indeed, the population has decreased every year since 2002 – from 4.2 million then, to 3.2 million in 2022, according to World Bank data.

For activists, “some of the things that we know need to be done cannot be done because we don’t have people to do it,” Porobić said. For example, she said she’d like to research a trend of police forces buying military-grade weapons. “There’s no time. There are no resources to do it,” Porobić said.

The European Union

Bosnia and Herzegovina became an official candidate country for EU membership in December 2022, but the European Union has long supported the country both financially and administratively.

Many activists and NGOs in Bosnia and Herzegovina see the EU as a force for good in the country and see membership as the end goal.

“I think that Bosnia’s path is the European Union and we should be there. I hope that one day we will be there. It’s a long path, but I think that the European Union has a positive impact and positive change,” Malešević said.

But Porobić said the EU lacks the moral authority to improve things in Bosnia and Herzegovina. “I think the moral high ground the European Union could take at some point is disappearing, because we do see some very, very worrying trends within the European Union.” Porobić pointed to the EU’s response to Israel’s war in Gaza and its policies on migration as examples of her concerns.

Porobić made that stance clear when EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen visited Sarajevo in the beginning of November, holding a sign accusing the European Union of “aiding and abetting genocide” in Gaza.

In some EU countries, authorities have cracked down on activists for protesting against Israel, Porobić said. In Germany, for example, police have arrested demonstrators for participating in pro-Palestine rallies. In Sarajevo, “we’re able to organise; we’re able to stand on the streets, to say genocide, to say apartheid in the same sentence as Israel,” she said. While activists in Bosnia and Herzegovina face restrictions on all sorts of expression, when it comes to criticism of Israel, Porobić said local activists enjoy more freedom than many in the EU.

Asked about the possibility of Bosnia and Herzegovina joining the EU, Kljajić’s response is short: “I wish that would happen.”

But if Bosnia and Herzegovina is to join the European Union, it will have to live up to 14 key priorities outlined by the EU Commission. These priorities include securing a functional democracy, the rule of law, fundamental rights and public administration reforms. EU representatives see the “foreign agent” law in the Republika Srpska as a move in the wrong direction.

“This law places unnecessary restrictions on the work of civil society and it is the kind of law that is more familiar in autocracies than in democracies who wish to join the European Union,” said Ferdinand Koenig, EU spokesperson for Bosnia and Herzegovina. “Our concern about this particular piece of legislation is that it is an attempt to control discourse in Republika Srpska.”

Koenig called the re-criminalisation of defamation a step backwards for Bosnia and Herzegovina, saying that criminal defamation in general is considered an outdated concept.

“But more than that, we have serious concerns about the rule of law in this country, the independence of the judiciary and how this particular piece of legislation will be used.”

“We understand that there needs to be some sort of legislation which regulates hate speech, which regulates issues of defamation and slander. But the question here is, as far as we can tell, that there is a real danger of misuse of this particular piece of legislation, and that’s where our concerns come from.”

With multiple NGOs concerned that the “foreign agent” law will impede their work, Koenig assured that the EU will offer its support. “We will continue, as the EU, to stand by civil society in this country whatever happens with this law,” he said.

The EU previously withheld funds allocated to the Republika Srpska after its government stopped recognising constitutional court rulings. The frozen funds for infrastructure projects amounted to €600 million. But despite condemnations, Koenig couldn’t say whether the EU would impose similar consequences on the Republika Srpska should the “foreign agent” draft law pass.

“We have underlined our expectation. It’s in the hands of Republika Srpska to act. We will see what happens next.”

‘Fear is not an option for us’

After UNSA Geto was attacked this May, Malešević and her colleagues began work to restore the space. They reopened the gallery, which continues to hold exhibitions and host events. “Fear is not an option for us,” she said.

Should the “foreign agent” draft law pass, Malešević vowed that UNSA Geto would continue its work. “This is one obstacle on our way to democratisation of society,” she said.

“We will work. We will be in illegal work if we need to,” Malešević said. “We’re not going to stop now.”